Written by SY (Simon Anderson)

"I am not actually a doctor," Dr. Iboga told me recently. "I am truly a dance teacher. Yet so many humans are just looping around and around in circles. So, first doctor, then Maestro!"

This wisdom from the ancient plant ally I've been walking with the past 12 years comes at a significant moment. After the Joe Rogan show featuring Bryan Hubbard discussing Ibogaine, I've been fielding many enquiries about getting this medicine into the world. Through the company I founded, Mpande Ethnomedicine, we've been preparing for this moment of sharing iboga medicines, including GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) Ibogaine, for a number of years. We’ve been working on healing protocols, supply chains, laboratory testing, extraction methods, and bringing the wood to market. But there's a deeper story here, one that begins with looping circles and ends with dance.

For twelve years, my path has been with iboga, not just ibogaine—my focus being working with total alkaloid extractions and, most often, the raw root bark itself. The wise, ancient ally. The Holy Wood. This has been more than profession and research; it's been an apprenticeship and a praxis. I've learned to be not an administrator of medicine, but handmaiden to a healing force far greater than myself.

We are long over the precipice of systemic crisis in mental and emotional health, particularly in the collective West, but also rippling through the world. This isn't just a medical crisis—it's the inevitable outcome of late-stage capitalism, industrial disconnection, and what therapists might clinically term “Complex PTSD”, but what the rest of us would call a profound, soul-deep exhaustion. We're heartful, spirited, feeling, sensitive mammals trying to function in an industrial, materialist paradigm, and our bodies know it isn't working.

The current captured medical model approaches this crisis like a mechanic maintaining equipment: just enough oil to keep the gears turning, just enough maintenance to prevent total breakdown. Psychiatric medications don't aim for healing—they aim for functioning. They are the WD-40 of the matrix, reducing the friction between our wild, embodied selves and the mechanical demands of modern culture. They don't bring lasting healing, wellness, joy, or connection to our aliveness. They can't; that's not what they're designed for… I’ll stop there before the pile of soapboxes becomes precarious.

And then we "discover" Ibogaine.

Here's a compound that seems to work almost miraculously, for all mental and neurological conditions but most notably for addiction—itself a response to trauma, a coping mechanism for unbearable pain. Ibogaine offers a window, an off-ramp from the endless loop. It gives us space to make amends, to sort through our spiritual wreckage, to face our deep, abiding pain with clear eyes.

And so we hail the remarkable silver bullet.

But we've been here before. We have been sold carefully crafted silver bullets, each one leaving massive unintended consequences in its wake. The very opioid crisis that Ibogaine now addresses was built on a foundation of previous "miracle cures". Heroin—its very name from the German "heroisch" (meaning heroic)—was Bayer's wonder drug of 1898, promising to cure morphine addiction. And morphine? That was the 19th century's answer to opium addiction, leading to what Civil War veterans called "the Army disease". Opium itself as laudanum was the Georgian and Victorian era's cure-all, prescribed for everything from anxiety to babies’ teething pains.

We long for the solution to our pain, the quick one, the one that requires little work: the magical, miraculous silver bullet.

In legend, the silver bullet was the only thing that could kill a werewolf. The werewolf—our wild, untamed, moonlit self—couldn't be killed by normal means. Lead bullets passed through it; iron couldn't pierce its hide. It took silver, pure and refined, to destroy this creature of instinct and power.

But what if the werewolf isn't the enemy? What if it's the last remaining fragment of our unbroken self, the part that still remembers how to howl, how to run in packs, how to live in harmony with cycles of moon and blood and season? What if our desperate addiction to seeking quick fixes is really our repeated attempts to kill the last wild parts of ourselves, to finally become fully domesticated livestock?

Perhaps, instead of seeking new and better ways to kill our wild creature, we should create a world where wild creatures are welcomed—where there's enough liberated space for all our untamed aspects, enough freedom to run naked under the full moon (and not just at Burning Man!), enough respect for the wisdom that lives in fur and fang and instinct.

All the talk of bullets and the great struggle between these forces of freedom and control is all very martial. When I shared with my wife my military metaphors for the work ahead—deploying iboga/Ibogaine treatment at scale—she winced at the violence of the language. My first response was ironic: "I'm a guy, get over it." But there's something deeper here.

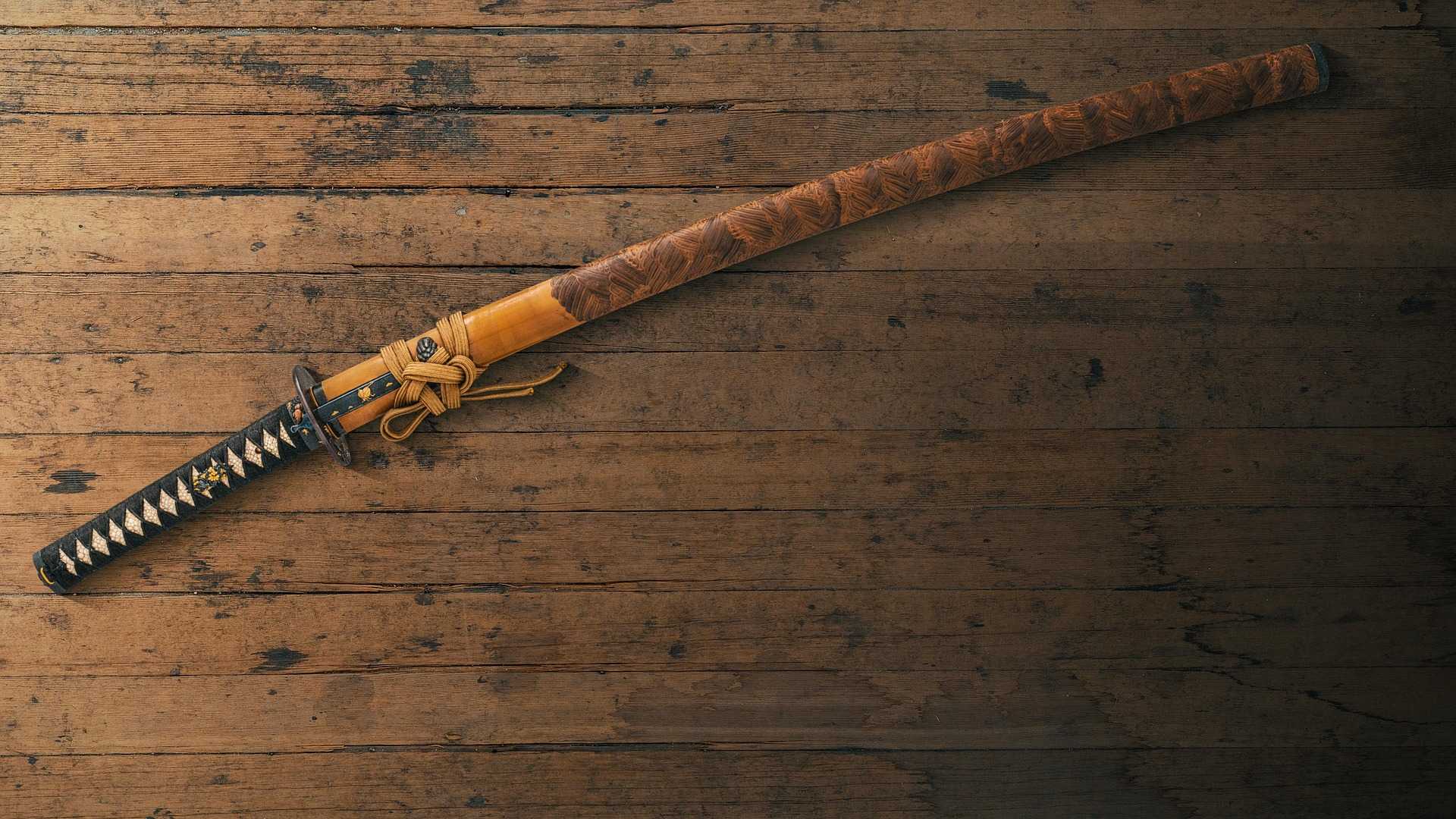

In the face of a captured medical system, a broken paradigm of care, perhaps this is a campaign—but we must choose our warrior way wisely. The way of the Kalashnikov or the way of the Katana.

The Kalashnikov transformed irregular warfare through brutal simplicity and accessibility. It is a weapon that a teenager with 20 minutes training can use to wreak havoc. Its creator, Mikhail Kalashnikov, wrote to the Orthodox Church near the end of his life: "My spiritual pain is unbearable. I keep having the same unsolved question: if my rifle claimed people's lives, then can it be that I am guilty for people's deaths?"

Then there's the Katana—the genuine variants are weapons forged with such deep consciousness that the making of them is a spiritual practice. These swords were not tools. They had names and characters. They were treated as allies and related to as powerful alive entities in their own right. Such a weapon requires decades to master, its unsheathing is a moment of profound significance, and its use is governed by a code of honor that we instinctively respond to.

Sometimes there is no choice but to "continue diplomacy by other means". Sometimes, unfortunately, we do need War as a last resort to put things in their right place. But in going there, we can choose a path of honor or a path of expediency.

As we stand ready to bring this medicine to the mainstream, to bring this healing to a wounded world, which path will we choose? I recently spoke to researchers preparing a clinical trial protocol where Ibogaine would be administered without any sacred container, without ritual space, without experienced guides connected to the wisdom of a tradition. It was to be just another pharmaceutical in a sterile room. This is how we lose our way. We start to notice the outcomes are less profound. We start to believe semi-synthetic and synthetic variants are ‘just as good’. After twelve years of witnessing profound healing through sacred work with the wood, seeing it reduced to a clinical intervention feels like watching a symphony performed with a single instrument. Will we deploy Iboga like a tool—standardized, simplified, stripped of ceremony and context? Or will we choose a path of honor?

Currently, we’re not heading in the right direction. The surge of publicity around Ibogaine has triggered a rapid influx of undertrained providers, particularly in Mexico. My highly skilled colleague Rocky, who has successfully facilitated almost a thousand opiate detoxes without a single death, puts it bluntly: “It’s chaos, Sy. We’ve gone back 20 years. There’s no preparation, no integration—just one-and-done marketing and mindset.”

The weight of this responsibility sits heavy on me as I lead an ethnomedicine company through these waters. We must use the levers of capital—there's no other way to reach the scale of healing needed in this crisis. Yet if we approach this growth without maintaining sacred integrity, without honoring the traditional ways, we risk recreating the very paradigms of extraction and dominance we seek to heal.

There's an obligation here: to honor those who shared this medicine before: the Central African forest peoples, the Bwiti practitioners’ tradition, and all those who have worked with and shared this medicine across generations. And even more fundamentally, we must honor the African equatorial forest itself—the biological and spiritual matrix from which this healing and teaching agent emerged. Every business decision, every scaling choice, must somehow balance these sacred duties with the urgent need to reach those who are suffering.

The truth, as Terence McKenna reflected, is that "the imminence of the mystery is breaking through all the structures of denial... The way to make this birth process smooth—the way to bring it to a conclusion that will not betray the thousands and thousands of generations of people who suffered through birth, disease, migration, starvation, and lonely deaths—is to redeem the human enterprise…"

We stand as antennae to the transcendental other, like Iboga's dance students learning steps we've forgotten or perhaps never knew. Together, we can create what McKenna called "an arrow out of history, out of time, perhaps even out of matter [or materialism - SY]—that will redeem the idea that humanity is good."

This is our opportunity: to transform the human experiment from an endurance of suffering into an expression of our highest potential. Not through silver bullets or quick fixes, but through the patient work of healing—healing that honors both our wildness and our wisdom, our need for relief and our capacity for transformation. The dance teacher is waiting. The looping is breaking. The music of possibility is beginning to play.

The question is: are we ready to learn the steps that will take us beyond the loop and into the dance of life itself? That's the opportunity.

Viva the Holy Wood!

Viva Maestro Iboga!